Many Christians today function as “New Testament Only” Christians. They apply little to no effort to understand the Old Testament and its application to our lives today. After all, we now have Jesus and the New Testament… so out with the old and in with the new, right? Ironically, the novel attempts to “unhitch” from the Old Testament is linked to the Marcion heresy dating back to the Second Century.

We must be “whole Bible” Christians. All of Scripture is profitable for us (2 Timothy 3:16). Let us not forget that when Paul penned those words, he would have been primarily referring to the Old Testament.

This series of articles seeks to help Christians make sense of the Old Testament and its continuing validity and application to our lives today. Here’s what we’ll be covering in this series:

- THE PENTATEUCH – The Patriarchs, Sinai Covenant & Decalogue

- THE TORAH (Part 1) – Tabernacle, Sacrifices, Priests, Feasts and OT Worship

- THE TORAH (Part 2) – Law & Covenant, Promised Land and Foreshadowing

- THE GOSPELS – Matthew, Mark, Luke & John

The goal is to show you the interconnectedness of the Bible’s message from the Pentateuch (the first 5 books of the Old Testament) to the Gospels (the first 4 books of the New Testament). This will not be an exhaustive explanation of all the material in the Pentateuch and Gospels. Rather, the goal here is a helpful big-picture overview that will give you the context you need to study and make sense of them on your own.

Understanding God’s relation to humanity through Law and Covenant has to start from the beginning to Sinai and beyond. This article will overview the Patriarchal period, the Pentateuch, and the Sinai Covenant & Decalogue.

The Key to Interpreting the Law

At the end of Luke’s Gospel, in chapter 24, we have the story of two disciples walking on the road to Emmaus. They’re heartbroken because their master and friend, Jesus, was dead and all their hopes were dashed to pieces. However, a stranger appears to them on the road and starts saying some strange things to them.

Instead of sympathizing with them, he rebukes them:

“O foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?”

Luke 24:25

The real problem of these disciples was that they did not understand the Old Testament. So, he helps them to understand:

“And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself.”

Luke 24:26

This stranger was Jesus.

Just as the disciples didn’t recognize how the Old Testament spoke of him, they didn’t recognize him along the Emmaus way until he opened up their minds to see it. Jesus begins with Moses and all the Prophets to interpret and explain to the disciples on that dusty Emmaus road the things that were actually pointing to him throughout the Old Testament. He explained how these things found their ultimate fulfillment in Christ and their purpose was to point him and His Kingdom. As he did this, a remarkable transformation happened to them. They said, “Did not our hearts burn within us while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the Scriptures?” (v.32)

This passage shows us that we need the Scriptures to be “opened up” to us—to see the connections and glories they reveal. Similar to those disciples, many modern Christians need help to understand how the Old Testament points us to Christ and the arrival and expanse of His Kingdom.

Christ is the Key

The whole Old Testament finds its culmination in Jesus Christ’s life, death, resurrection, ascension and his inaugurated, expanding Kingdom. He is the key that unlocks the riches of the Old Testament. He is the substance of what the Old Testament foreshadowed.

Again and again, God spoke to His people in the Old Testament about Christ through symbols and shadows which were appropriate to them and their context and circumstances rather than immediately understandable to our modern context. This is why the Old Testament often seems foreign to us and we miss its significance. It takes some work to rightly understand the Old Testament and its context. Many may think the hard work is not worth it, but you don’t find gold without some digging! And what we have to find is far more precious than gold (Psa. 19:10).

The Old Testament starts the big story of redemption that God has written throughout history. It forms the beginning of the story that lays a lot of the important groundwork we need to fully understand the latter half of the story. Just like you can’t properly appreciate a novel if you just jump into the second half, we cannot fully understand the New Testament without spending the time in the Old Testament.

We have a threefold task to understand the Law of Moses:

- In its own historical context and what would it have meant to the original recipients.

- As the beginning of God’s Story of Redemption which the New Testament completes.

- In our context, considering how we obey and apply God’s word to ourselves today.

As with the two disciples on the Emmaus way, when the Old Testament was opened up to them, they were in awe, amazed and overwhelmed by the beauty of God’s big story. I pray that this is what the Lord would help each of us to experience this.

The Old Testament and the Pentateuch

The Jewish Old Testament was also called the TaNaK—which stood for the 3 categories of books: Torah, Nevi’im and Ketuvi’im—Hebrew for the Law, the Prophets and the Writings. While I don’t endorse everything the Bible Project puts out, this short overview is helpful for understanding the broad divisions of the TaNaK.1 Some of the content the Bible Project produces are wonderful and helpful summaries of Biblical books and passages. However, some of their theological positions are at odds with a Reformed understanding of theology, and I would argue are out of step with a faithful reading of Scripture. This is too big of a topic to get into in this article, but please understand that my usage of some of their content in this series is not a wholesale endorsement of their content. There are others who have outlined some issues with the Bible Project and its co-founder Tim Mackie including denying Hell and penal substitutionary atonement and compromising on LBGTQ issues. As with all content, we must be good Bereans (Acts 17:11) and test all things (1 Thess. 5:21).

Today, we will look at another grouping of books in the Old Testament: the Pentateuch.

What is the Pentateuch?

The word “Pentateuch” comes from two Greek terms, penta (πεντα), meaning ‘five’ and teuchos (τεῦχος), meaning ‘book’. So, the word simply means “five books”. It refers to the first five books of the Old Testament (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy) which were written by Moses.

According to the Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible,

“The Pentateuch begins with the creation of the universe and records God’s dealings with mankind in the Garden of Eden, his preparation of a seed-bearing line (the patriarchal stories), and the formation of the nation Israel. A substantial portion of the Pentateuch consists of laws governing the religious and civil life of the theocratic nation.”

(Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, pg 1639)

Thus, what we find are the stories of beginnings and origins in Genesis, the history of how God saved His people in Exodus, how He wanted His people to live and worship in Leviticus, how He sanctified His wayward people Numbers, and how He reminds His people of their history and His standards for them in Deuteronomy. All of this shows us God’s intimate care for His people as a Good Father and Shepherd to them, even though they are often unfaithful and rebellious.

As we read these histories in Scripture, while we must bear in mind their historical context—that they were written to a people long ago in a very different context to our modern day—we can also glean timeless truths about man, God and the world He has made that we can apply today.

While the Old Testament scriptures were not written TO us, they are FOR us.

Creation

God’s story of redemption starts at creation. There’s much we can get into on the creation story, such as the nature of man as created in the image of God, creation ex-nihilo (out of nothing), etc. However, we’ll be focusing specifically at themes and topics related to understanding God’s law within redemptive history.

Here are the two important themes we must understand from creation:

1. Order & Life

First, in Genesis 1, we see that God brings order from disorder.

We see in the beginning, after God speaking things into existence, that the earth is a formless and chaotic place. Then, in the days of creation, God brings order to the disorder of the unformed earth. It is important to note that He does not just instantly create an ordered cosmos, but rather works in the unrefined creation to bring it into order. In the first 3 days, He separates the various aspects of the earth’s surface—the sky, atmosphere, waters, land, etc. (Gen. 1:1–10)—to create the environments which He then fills with the creatures that inhabit them in the following 3 days (Gen. 1:11–27). He prepares the suitable environments to sustain life in the sea, air and land.

Secondly, we see that God brings life from non-life.

He causes plants and animals to spring up from the earth, and he forms humans out of the dust of the earth. This is something that naturalism cannot explain. There are no natural processes by which non-life becomes living. Life is the gift of God’s generous hand.

These two concepts of order and life are important aspects of God revealed in creation which are important for us to keep in mind in order to appreciate many parts of the Old Testament Law. We’ll see these themes come up many times as we read through the sections of the Law.

In terms of the historical context of Genesis, we must consider that the pagan cultural context the Israelites would have been surrounded by believed that the world was the product of warring deities who were part of creation. There were beliefs that the physical world was something to be escaped from and other myths of cosmic chaos where man and the world were accidents of the activities of the gods.

Thus, the Genesis account stands in stark contradiction to what would have been the original readers’ cultural context. It had a strong polemical force stating instead that the all-powerful, transcendent God created everything out of nothing, and created it good and with a purpose. Man was created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27)—to rule the creation on His behalf. This is still true today of Genesis. It is a powerful apologetic against the prevailing myths of our day such as evolution. Its message is still as relevant to us as ever—we must know our true origins, who we are, and how and why God has created the world.

2. The Fall

The Fall expresses the antithesis to God’s giving of order and life to creation. It is the undoing of God’s good work in creation.

All of creation is covenantally related to God as its Creator and Sustainer. Many theologians call this original covenant with man the Covenant of Works—whereby God requires of Adam and Eve perfect obedience to merit everlasting life (Gen. 2:16–17).

God is the source of life and order. So, disobedience and separation from Him results in death and disorder.

Thus, when Adam and Eve ate of the forbidden fruit, their relationship and connection to God are cut off. They broke their covenant relationship with God and inherited covenant curses instead of blessings (a concept we will return to later). They die in a spiritual sense immediately as they are cut off from the source of life, and physical death is a natural consequence of this spiritual death.

This is an important point to note here. The spiritual and the natural are intimately interconnected (something many moderns today do not adequately appreciate). Thus, spiritual death results in physical death.

Furthermore, we see that in Adam and Eve’s sinful rebellion, not only do they reap death instead of life, but they also cause disorder instead of order. Because of their sin, God curses the ground and creation, and Adam and Eve both receive curses that disorder their lives.

The Fall explains why our world is broken and why evil an sin exist today. We all have inherited a sinful nature from our first parents, Adam and Eve. God originally gave to them the Dominion Mandate (Gen. 1:28–30), to steward His creation, make it fruitful, and fill the earth with more of His image bearers. However, since the Fall, the creation itself is now under a curse—making it harder for humanity to be fruitful and take dominion. They each receive curses in relation to their main are of dominion and fruitfulness—working the ground for the man, and childbirth for the woman (Gen. 3:16–19). We also see that man and creation are intimately connected. Because Adam was appointed to be God’s vice-gerent over creation, his fall has ripple effects over all those under his covenant headship and care.

So, we see that since the Fall, God’s life and order have been disrupted in creation and humanity. This is the second truth we must keep in mind to understand the Law. We will also see this theme come up multiple times in the Law.

The Patriarchal Period

Next, we’ll briefly look at what is known as the period of the Patriarchs.

The Patriarchal Period is:

“Period of time during which the biblical fathers of Israel lived. The Bible tells of long-lived patriarchs before the flood (Gn 1–5); of Noah (Gn 6–9); and of a line of patriarchs after the flood (Gn 10; 11). However, the word in the narrower sense usually refers to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Gn 12–36), with the addition of Joseph (Gn 37–50).”

(Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, p.1620)

This period of time is the history of the forefathers of the nation of Israel, God’s chosen people in the Old Testament, before the nation of Israel was formed through God’s covenant and law. Its key themes and events are important for us to understand the historical background of the law.

Key Events and Themes

The narratives about the patriarchs focus on promise, covenant, election, and faith. They serve as a way to teach us about these truths through engaging stories about real people we can relate with. Motifs such as childlessness, sibling rivalry, deception, and alienation are also present.

These motifs show the patriarchs as humans who struggled when God’s promises did not come to immediate fulfillment.

Sound familiar? These are still struggles that are common to us today.

The themes of promise, covenant, election and faith are the foundation of the giving of the Law. Look out for these as you read through the Old Testament Law.

The Abrahamic Promise

The promises of the patriarchs are given initially to Abraham, and transferred successively to Isaac and Jacob (later called Israel). All of these Covenant Promises contain five elements:

- (Gen 12:2)—God will make Abraham into a “great nation”

- (Gen 12:2)—God will bless him

- (Gen 12:2–3)—God will make him influential (his name will be “great” and he will be a “blessing” to the world)

- (Gen 12:7)—God will give the land of Canaan (i.e. Palestine) to him and his descendants

- (Gen 13:16; 15:5)—His descendants will be many

The last two promises, given after Abraham arrived in Canaan, are repeated many times in Genesis (Gen 13:14–18; 15:7, 13–16, 18–21; 17:6–8; 22:15–17). They are presupposed by the first three elements—a nation requires territory and a population. One could summarize the promise as pertaining to land and seed—two important concepts that can be traced throughout the Bible.

This is important for us because the promise to Abraham is the basis of the Mosaic covenant in Exodus, where we find the ‘Law of Moses’.

“And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. God saw the people of Israel—and God knew.” (Exodus 2:24-25)

Note the highlighting of God “remembering” His covenant with the patriarchs. This does not mean that God had forgotten and suddenly something jogged His memory. Instead, it denotes when God takes action based on His previous convenantal agreement.

God’s mighty saving acts in Exodus are the outworking of His faithfulness to the promise He made to Abraham. So, the Mosaic Covenant is a result of God’s prior choice and love for the patriarchs (election).

Although we no longer live in the time period of the Old Testament patriarchs, this principle still stands for us today.

Fathers (patriarchs) can set the trajectory for generations to follow and God deals covenantally with us. God has ordered life such that the father is the head of a household. This is not optional. The father/husband is the head of the household. The only question is whether or not he will be a faithful head and bring blessing upon his household, or an unfaithful one who will bring curse.

As we read the Old Testament narratives of the patriarchs, one of the things we are meant to see is how the father’s decisions (both good and bad) had ripple effects for their posterity and learn to take our roles as patriarchs and fathers very seriously.

Men, your leadership (or lack thereof) will have implications for generations to come. Ladies, this is true—so choose your man wisely, and support and encourage him in building a godly home. As we read the narratives about the patriarchs, we are to glean wisdom both from their wisdom and from their foolishness. If you track the narratives fully, they illustrate to us the long-term effects of sin and obedience so that we can learn from their stories.

Law & Covenant

In order for us to understand Biblical Law as a category, we must understand that it is intricately and inseparably connected with covenants. I’ve been using the words “law” and “covenant” many times here. So, we must understand what we mean by biblical ‘law’ and what is a ‘covenant’. Only then we can put the two together to get the big picture.

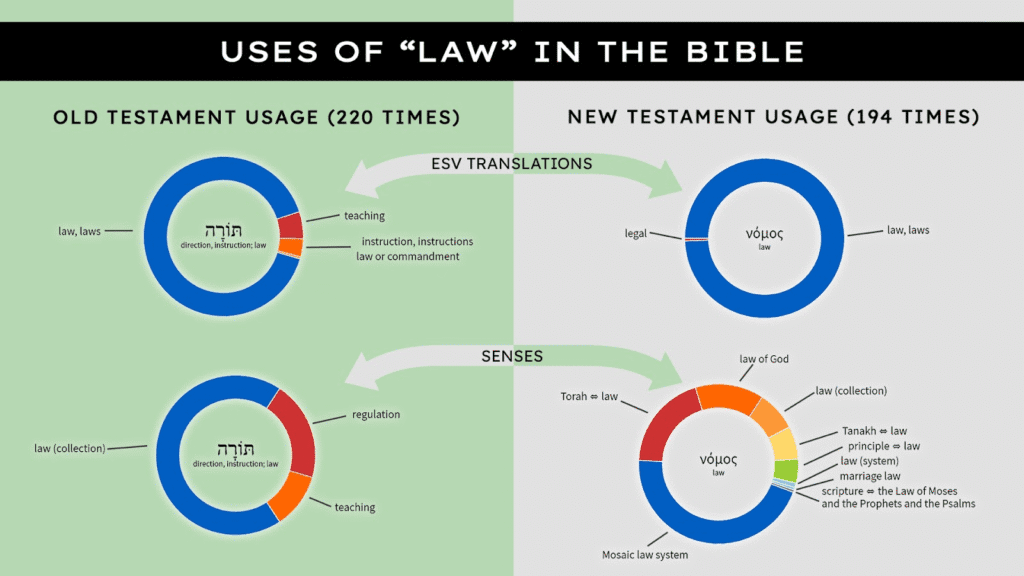

Law in the Bible

The topic of “Law” in the Bible is pervasive throughout all of Scripture. It occurs 220 times in the Old Testament and 194 times in the New Testament.

So, it is sad that many Christians today ignore a thorough study of the Law!

The Law is vital to understanding the Bible’s message as a whole. Perhaps this is one reason for the epidemic of Biblcal illiteracy in churches today. Many modern churches foresake studying God’s Law.

It is for good reason that the longest Psalm in the Bible is a meditation on God’s Law. The Psalmist reminds us:

Blessed are those whose way is blameless,

who walk in the law of the Lord!

Blessed are those who keep his testimonies,

who seek him with their whole heart

(Psalm 119:1–2)

So, our prayer should be:

Teach me, O Lord, the way of your statutes;

and I will keep it to the end.

Give me understanding, that I may keep your law

and observe it with my whole heart.

Lead me in the path of your commandments,

for I delight in it.

(Psalm 119:33–35)

Remember that:

The law of the Lord is perfect,

reviving the soul;

the testimony of the Lord is sure,

making wise the simple

(Psalm 19:7)

How different a view of the Law this is than what many modern Evangelicals have!

While a thorough study of the Law is not the focus of this series, I’ll attempt to at least give a basic introduction here.

Part of the reason why the topic of ‘law’ can be confusing is that the Old Testament has many words for the concept of God’s Law.

The most general word is Torah, which signifies instruction of any kind: religious and secular, written and oral, divine and human.

“On occasion torah may be legitimately translated as “law.” However, its everyday meaning is illustrated by the book of Proverbs, which applies the term to the “instruction” that the wise provide…”

(Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p.1015)

Some words for the law in the Old Testament are:

- Words (cf. Ex 24:3; 34:27) – duties of man to God (eg. 10 Commandments)

- Judgments (cf. Ex 24:3) – civil regulations and duties

- Ordinances (cf. Lv 3:17; Nm 9:12, 14; Dt 6:2) – cultic regulations or ceremonial laws (especially in Leviticus), or any expectation or regulation

- Command(ment)s (cf. Dt 5:28; 6:1, 25) – regulations given by a higher authority

Other synonyms for law in the OT:

- Decrees (cf. Lv 10:11; Nm 30:16; Dt 4:1)

- Precepts (cf. Psa. 119)

- Stipulations, Requirements (cf. Dt 4:45; 6:20)

- The “Way(s)” (cf. 1 Kgs 2:3; Pss 18:21; 25:9; 37:34).

So, whenever you see these words in your Bibles, it is talking about some aspect of God’s law.

As you’ve probably realized by now if you’re familiar with your Bible, it talks about the Law quite a bit!

What was the purpose of the Law?

Israel was a theocratic nation—meaning that they were ruled by God—and thus they needed a legislative corpus from God to govern them.

Consider this: Israel had been rescued from 400 years of slavery in pagan Egypt. They had many generations living and assimilating to the pagan culture of Egypt—its customs, values, ethics, morals and laws. As a result, they did not have an intuitive grasp on the True God’s holiness, justice, righteousness, love and forbearance which He required of them. They had adopted the pagan ways of Egypt and needed God’s revelation to learn His divine will.

In the Exodus, God had taken Israel out of Egypt. Through the Law He gave them, He was taking Egypt out of the Israelites.

The Law God gave to them was to govern every aspect of their lives—and therefore it would transform and shape every aspect of their lives. Reshaping them into His people, molded by God’s values, ethics, customs, and morals.

This law was mediated to them primarily by Moses.

“However, Moses and the prophets emphasize that the purpose of the Law is not strict adherence to the Law for its own sake (legalism) or for a reward (Pharisaism). Keeping the Law is an act of devotion to God, for the sake of God.

…The Law of God is his means of sanctification. He consecrated Israel by an act of grace, and he required Israel to remain holy.”

(Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, 2, p.1316)

The purpose of the Law was to help transform God’s redeemed people into maturity.

“The saints in the OT who loved God delighted in his Law as a reflection of his will; saw in it God’s fatherly concern for his children to learn to love, to be just and righteous, and to walk humbly before him (cf. Gn 17:1; Mi 6:8). God’s goal was to train individuals in Israel to maturity, freedom, and sonship.

(Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, 2, p.1317)

We will see more about the purpose of the law later in this series.

God’s law was meant to help sanctify, not to save, His people. This is one of the reasons God’s Law is still valuable to us today.

To sanctify simply means, “to make holy” or to “set apart”. Israel, that is, God’s people, are meant to be set apart for Him alone. They are to be distinct from all the other people and nations.

Here is another helpful video summary.

Now that we’ve taken a brief look at the Law, let’s look at the concept of “covenant”—a core theme in the Bible.

Covenant

There is much confusion and unclarity amongst many modern Christians today about what exactly is a covenant. Perhaps part of the struggle is that we no longer live in times where covenants are normally spoken of. Our age is not an age of covenants but of contracts—such as business contracts—and so, we default to erroneously equating a covenant with a contract. However, though there may be some similarities, a covenant is not simply a contract.

According to Bible Scholar, Dr. Vern Poythress, professor of New Testament, biblical interpretation, and systematic theology at Westminster Theological Seminary:

“A covenant is a formalized pact with sanctions… When such pacts were made between human beings, the parties expressed loyalty to one another and spelled out their mutual obligations (e.g. Gen. 21:26-31; 26:28-30; 31:44-54). They also took an oath calling down curses on themselves if they did not keep the terms of the covenant.”

(Poythress, The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses, p.63)

A covenant is a formalized pact expressing loyalty between two parties to one another based on prior relationship, outlining their mutual obligations, blessings and the curses/consequences for failing to keep the terms of the covenant.

All covenants necessarily had three parts:

- IDENTIFICATION – An identification of the parties involved and recounting the previous relational interactions between them

- STIPULATIONS – Specification of their mutual obligations

- SANCTIONS – An oath indicating how God would reward obedience and punish disobedience to the stipulations

Many covenants also had some sort of sign or symbol associated with them to illustrate the relationship, or the sanctions, or simply as a seal or guarantee of covenant faithfulness. For example, circumcision in the Old Testament or baptism and communion in the New Testament.

Hittite Suzerainty Treaties

Historically, in the Ancient Near East, it was a common practice among Hittite (pagan) kings to make pacts with other kings called suzerainty treaties. The powerful king, the suzerain, made a treatise or pact with the lesser, subordinate ruler, called the vassal. The vassal promised loyalty, obedience and support to the suzerain, and in return, the suzerain promised blessing and protection.

In these treaties, they would write up a document that contained:

- Preamble identifying the parties

- Historical Prologue explaining their relationship

- Stipulations specifying the duties of the vassal

- Provision for a written copy to be deposited in the vassal’s temple and periodically read publicly

- List of witnesses

- Sanctions – a list of curses and blessings for violations or loyalty to the treaty.

This historical context provided a ready analogy for Israel to understand their relationship with the True God. It was something from their historical context that the Israelites would have readily understood. The Biblical Covenants have many similarities with these suzerainty treaties. Or put more accurately, God’s Kingship is the origin and pattern for all earthly kings. These pagan suzerain treaties were simply a fallen reflection of the true original.

Let’s take a look at an example.

DEUTERONOMY: An example of the Old Testament Covenant

The whole book of Deuteronomy is organized as a covenant renewal ceremony.

If we don’t understand the context of the covenants (which mirror the Hittite treaties), we would miss the significance of this and wonder why Deuteronomy just repeats a lot of things from the earlier books.

The structure of the book can be divided like this:

- A Preamble – identifying the parties (1:1-5)

- Historical Prologue – recounting the prior relationship of God and His people (1:6-4:49)

- Stipulations – list of duties (5:1-26:49)

- A written copy was placed in ark in the temple/tabernacle (10:1-5)

- Sanctions – blessings & curses (27:1-30:20)

- Covenant Continuity – Moses sets up Joshua to take his place, and charges the people to be faithful to the covenant and blesses the people before his death (31:1-34:12)

The analogies to the practices of the Hittite Kings continues with what was done with the covenant documents (the Ten Commandments). Like the Hittite Suzerainty Treaties, two copies were produced on the two tablets of stone. However, unlike the Hittite practice, where one copy was given to the vassal and the other to the suzerain to keep in their separate temples – both copies were placed in the tabernacle since in Israel’s case, God (the Suzerain) dwelt with Israel (the vassal)! They alone were put inside the ark of the Covenant (Deut. 10:1-5), whereas the rest of the instructions Moses received from God was put beside the ark (Deut. 31:24-26). So, the Ten Commandments were very closely understood to be tied to the Covenant God made with Israel.

The tabernacle had two cherubim on the ark and woven into the pattern of the curtains – representing royal guards to God’s throne room. The tabernacle also used imagery from creation in the lampstand, bread, and the details of the decor including pomegranates and other garden-like imagery. All these details together show us that God is indeed the Great King over both Israel (His people) and all of creation. The tabernacle represented God’s heavenly throne room from where God sits as King (cf. Isa. 6:1-4). From His throne come all His utterances. Thus the “Ten Words” were stored in God’s “footstool” of His throne – the ark of the covenant. The tabernacle and temple to the Israelites represented God’s presence with them which foreshadows Christ – Immanuel – “God with us.”

In delivering this ‘Covenant Renewal Ceremony’ in Deuteronomy, Moses acted like the King’s emissary – reminding the people of God’s covenant with them and the blessings and curses attached to it. This was the function of the OT prophets – which we will explore more later in this series.

In the next part of this series, we will focus more on the details and significance of the tabernacle and temple. For now, we will look briefly at each of the Ten Commandments and their meaning.

God’s Covenantal Relationship with His People

The following three elements of covenants are used in God’s relationship to His people in the Old Testament, Israel. His relationship with His people, then, can be said to be ‘covenantal’ since it involves:

- PERSONAL PRESENCE – Corresponding with His self-identification to and relationship with His chosen people

- DIVINE ORDER – Corresponding to His covenant stipulations

- GOD’S POWER to bless or curse and to make atonement – corresponding to the covenant sanctions.

If you pay attention as you read the Old Testament, you’ll notice these elements when God speaks of His covenant with His people. This paradigm has not changed—God still relates in a covenantal way with His people today through Christ (as you will see below).

The relationship between Law & Covenant

Much of Biblical Law occurs within the context of Biblical Covenants. That is, in the context of God’s covenantal relationship with His people. Thus, the laws (or covenantal stipulations) are not how people establish or maintain their relationship with God, but rather are the result of them already being in a covenant relationship with God. The Ten Commandments fit within the stipulations section of the covenant.

The Ten Commandments aren’t about how we become God’s people, but rather are given to us because we are His people. They presume a prior relationship with Him already.

The difference is this:

- It is NOT: do these things and keep these laws, then you’ll have a right relationship with God

- It IS: God, out of His love for us, has provided the way to have a right relationship with Him, therefore, this is the way we are to live in light of that

Covenant Through Christ

We will get to how Christ connects to the Old Testament and Law in later entries in this series, but briefly here, we can observe how Christ is the fulfillment of the whole Mosaic law and covenant in the Pentateuch:

- PERSONAL PRESENCE – Christ is God dwelling with His people – Immanuel – “God with us”. (cf. Col. 2:9; John 14:20-23)

- DIVINE ORDER – Christ’s character is the perfect pattern of righteousness as he perfectly kept the law of God for us (cf. 1 Cor. 1:30; Rom. 13:14)

- GOD’S POWER – Christ expresses God’s power to atone for sin (cf. Heb. 9:28; 1 John 2:2)

This is why Jesus spoke of the “New Covenant in his blood” (cf. Luke 22:20)—as Christians, we are still in covenant with God.

The Sinai Covenant

To properly understand the 10 Commandments, you need to understand the context of the Sinai Covenant.

After the last story in Genesis of Joseph rescuing the descendants of Abraham and Jacob (Israel) by offering them shelter in Egypt, some time passes and the Hebrews multiply greatly in Egypt under its prosperity. However, God’s promise to Abraham was not only that his descendants would be many, but also that they would inherit the Promised Land. Yet, at the end of Genesis, they are in Egypt. Furthermore, a new Pharaoh comes to power who didn’t know Joseph, and he starts to oppress the Jews since they seem to be a growing threat to him.

So Exodus starts off with this predicament: God’s people (Israel) are in Egypt, not in the Promised Land, and they are being oppressed by a tyrannical king. They cry out to the Lord and He hears them. And He acts through an unlikely hero—Moses—to rescue and deliver His people through many mighty acts. God sends plagues that challenge the Egyptian gods—showing He is the only supreme God—which eventually wears down the wicked king to release the Israelites. Then as they flee Egypt (with its riches in hand), Pharaoh chases them with his army, and God again rescues His people through mighty acts—splitting the Red Sea and drowning the Egyptian armies. (See Exodus 5 – 15)

Indicatives THEN Imperatives

It is only after these saving works of God that we arrive at the Sinai Covenant of Exodus 19–24. This is an important point to note:

God’s commands (imperatives) are always predicated on the description (indicatives) of His gracious saving work.

In other words, God first graciously acts to save, then tells His redeemed people how to live.

This is the framework for God’s law, and also for all of the Bible. This same pattern can be seen in the letters of the New Testament: the first half of the letter tells of God’s saving grace (the Gospel) and the second half tells us how we ought to live in light of that (commandments). If you flip this order, you end up with legalism—thinking you get to salvation by following the commandments. However, if you get it right, you get grace-driven, joyful obedience out of gratitude for God’s salvation apart from your good works.

From Old to New Testaments, this is the pattern of God’s salvation. Grace then Law. Salvation, then sanctification. This is how we ought to understand the 10 Commandments.

The Decalogue (10 Commandments)

The word “Decalogue” comes from two Greek words. The first, “deca” meaning ‘ten’ and the second “logos” meaning ‘word’ – so it means, “the ten words”. This was the common phrase that the 10 commandments was called – the ten words from God.

The Ten Commandments are unique in that God spoke them directly to all of Israel from the top of Mount Sinai, in contrast to the rest of the Law which was received through Moses. Only the Ten Commandments were written personally by the finger of God on two stone tablets (Exodus 20:1-21).

Note that before the Lord gives to Israel the Ten Commandments which are part of the Sinai Covenant, He reminds them first of His saving work (Exodus 19:3-6 & 20:2). They are to obey these commandments in light of the fact that God has already freed them from their bondage.

The first four commandments (the first table of the law) deal with our relationship to God, and the last six commandments (the second table of the law) deal with our relationships to other people.

The Ten Commandments are an expression of God’s holy character and order. As we go through them you will see the themes of order and life that we pointed out at the beginning of this article come up repeatedly.

1. YOU SHALL HAVE NO OTHER GODS (Ex. 20:3)

God is the sole LORD, Creator and source of life, so any competition with another supposed ‘god’ introduces disordered worship and leads to spiritual death. Every sin has the same root—idolatry—an elevation of something or someone above God. It is a disordering of God’s ultimate supremacy.

2. YOU SHALL NOT MAKE IDOLS (Ex. 20:4-6)

The second commandment deals with making images for worship. It expands on the first commandment by forbidding not only the worship of false gods, but also the improper worship of the True God through attempting to make images of Him. The attempt to make an image of God is inappropriate because it misses the fundamental character of the revelation at Sinai where on the mount, no image appeared (Deut. 4:15-20). It shows us that worship to God must conform to the order of God’s own revelation. We cannot invent ways to worship God, we must worship Him as He has commanded us to.

3. YOU SHALL NOT TAKE THE LORD’S NAME IN VAIN (Ex. 20:7)

Many think this command merely means not using God’s name as a swear word. While that is definitely part of it, it’s not all that this commandment means. This command enjoins us to protect the holiness of God’s Name which is the revelation of His character. Notice how God reveals His character through His name:

“The LORD descended in the cloud and stood with him there, and proclaimed the name of the LORD. The LORD passed before him and proclaimed, “The LORD, the LORD, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, but who will by no means clear the guilty, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.” (Exodus 34:5-7)

Thus, anything that maligns the character of God is taking His Name in vain. This also means that we, as God’s people, are not to do or say anything that would profane God’s holy character since we bear His Name.

4. REMEMBER THE SABBATH AND KEEP IT HOLY (Ex. 20:8-11)

This commandment is special in character in that it focuses on human relationship to God, but it also involves a creation pattern as well taken from the seven days of creation. It is a sort of mediating point between the commandments concerning God and the commandments concerning one’s neighbour. This commandment enjoins us to follow the pattern that God set by His own example in the creation week. It also shows us that God wants us to order our time and calendar. This is why historically, the Church has kept a liturgical calendar of celebrations, feasts, memorials, etc. It is a part of how we order and steward our time. This command also forces us to reckon with our finitude and need for rest.

5. HONOUR YOUR FATHER AND MOTHER (Ex. 20:12)

This is the first commandment dealing with our responsibilities to other humans. It makes sense that it would relate to the primary relationship of closest family. The family is the proper place for production of new life, and thus the preeminent form of protecting and honouring life which comes from God. Also, because parents have the primary responsibility to teach children about God and His law (Deut. 6:6-9), the parents represent the primary means by which the knowledge of and conformity to the divine order is to be passed on and preserved. An attack on parents then is an attack on God Himself. This is why Old Testament punishments concerning parents were so steep.

This commandment also teaches us that, as a part of God’s order, He has built hiarchy into the world—superiors and inferiors—to whom honour and obedience are due.

6. YOU SHALL NOT MURDER (Ex. 20:13)

Enjoins the preservation of human life as image bearers of God. The negative command not to murder also implies a positive responsibilty to protect life. This includes life in the womb all the way up to the point of death.

7. YOU SHALL NOT COMMIT ADULTERY (Ex. 20:14)

Enjoins orderliness of human sexuality—which is closely related to the creation of new life and thus is a natural consequence of the call to holiness. This is also why the penalties concerning sexual sin are so high. In just law, the severity of the penalty tells us something about the value of the thing it was meant to protect. Sex is sacred, thus it is guarded by this Law. By extension, this law also would lead us to safeguard things related to sex by use of modesty.

8. YOU SHALL NOT STEAL (Ex. 20:15)

Deals with the orderliness of human property since theft disorders the relationship of human ownership which is closely related to the dominion that humans have been given, which images God’s dominion over the world. This law also informs us about the right to private property. A law against theft would make no sense unless there was personal ownership. This is why systems that oppose private property rights like Communism and Socialism are inherently anti-Biblical.

9. YOU SHALL NOT LIE (Ex. 20:16)

Orderliness of human speech—truthful human speech imitates God’s speech and law. The Bible even goes as far as saying that “Life and death are in the power of the tongue” (Proverbs 18:21). God creates by speaking, and although we cannot create the way God does with words, words do have power. Thus, we are to guard our speech. This negative command not to lie also necessitates the positive command to tell the truth. Christians, therefore, should be unapologetic and unashamed truth-tellers.

10. YOU SHALL NOT COVET (Ex. 20:17)

This commandment demands orderliness of our desires and is the only commandment on the second table that deals with the heart. We can see murder, theft, and adultery—but we cannot see covetuousness. Jesus expands on this point by saying that all sin ultimately springs from the heart (Mark 7:20-23) and that breaking the other commandments starts in the heart (lust, hatred – cf. Matthew 5). Thus, sins like murder start with hatred, and adultery with lust. God doesn’t just want outward obedience but also inward genuineness.

Notice also that the order of the focus of the Ten Commandments transitions from heaven to earth.

The Ten Commandments form the basis for what is called the MORAL LAW. This is the basis of Christian morality.

THE PROBLEM OF SIN AND THE LAW

Notice that right after God has given to Israel His Moral Law—the Ten Commandments—their response is one of fear and trembling.

Now when all the people saw the thunder and the flashes of lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking, the people were afraid and trembled, and they stood far off and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen; but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.” (Exodus 20:18-19)

When faced with the perfect moral law of God, the people realize their problem—they cannot perfectly keep this Law because of their sin. They feel afraid in the presence of a Holy God who has given them His Holy Law. This is the impact that God’s perfect law has on us, even today. When we look at it, and then look at ourselves, we realize how much we don’t live up to it and can’t live up to it. God’s law acts like a mirror to show us our own dirtiness. We feel guilty.

What is the solution?

We all feel the guilt of sin when we break God’s laws. Something deep inside us cries out that we are not worthy of approaching or seeing God’s holiness and glory when we are stained with sin. We need something to look to in order to take away our sin and the feeling of our guilt. God knew this and we find very soon after the Israelites shrink back in fear of God that He gives them the means by which their guilt can be dealt with and something to look to for the solution to their sin.

Just one verse later, Moses reassures the people:

Moses said to the people, “Do not fear, for God has come to test you, that the fear of him may be before you, that you may not sin.” (v.20)

Then, as Moses draws near to God in the thick darkness (v. 21),

And the Lord said to Moses, “Thus you shall say to the people of Israel: ‘You have seen for yourselves that I have talked with you from heaven. You shall not make gods of silver to be with me, nor shall you make for yourselves gods of gold. An altar of earth you shall make for me and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep and your oxen. In every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you. (Exodus 20:22-24)

God introduces the sacrificial system to them – where an innocent animal would be sacrificed in place of guilty sinners as a substitute for them on an altar. This is what we will turn our attention to in the next article in this series.

WATCH

Before we finish this first article, here are 2 quick resources to help you further understand what we’ve covered.

Recommended Resource

The Ten Commandments: What They Mean, Why They Matter, and Why We Should Obey Them by Kevin DeYoung

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first article in this series. In future articles we will cover:

- THE TORAH (Part 1) – Tabernacle, Sacrifices, Priests, Feasts and OT Worship

- THE TORAH (Part 2) – Law & Covenant, Promised Land and Foreshadowing

- THE GOSPELS – Matthew, Mark, Luke & John

Please consider sharing this article if you found it helpful.

SDG.

Footnotes

- 1Some of the content the Bible Project produces are wonderful and helpful summaries of Biblical books and passages. However, some of their theological positions are at odds with a Reformed understanding of theology, and I would argue are out of step with a faithful reading of Scripture. This is too big of a topic to get into in this article, but please understand that my usage of some of their content in this series is not a wholesale endorsement of their content. There are others who have outlined some issues with the Bible Project and its co-founder Tim Mackie including denying Hell and penal substitutionary atonement and compromising on LBGTQ issues. As with all content, we must be good Bereans (Acts 17:11) and test all things (1 Thess. 5:21).